Artist Allan Rohan Crite’s vision of Black Boston

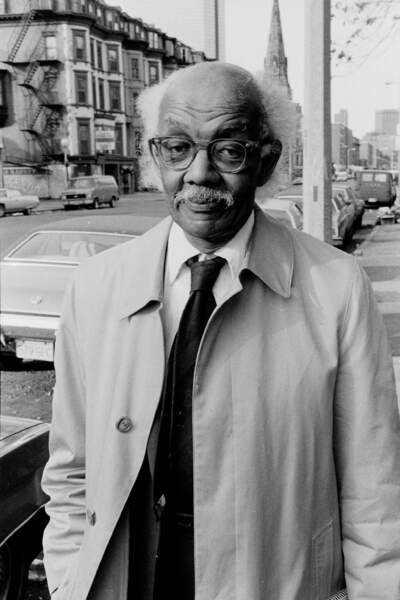

Artist Allan Rohan Crite captured Boston life in a singular way.

Renowned for his depictions of the city’s Black communities, he focused particularly on Boston’s South End and Lower Roxbury neighborhoods. Crite’s artistic practice is marked by his inquisitiveness and innovation, and the range of materials he embraces.

His paintings and works on paper elevated Black life and spirituality during a period of great social change. A major survey of his prolific output opens at two major Boston institutions Thursday, Oct. 23. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and the Boston Athenaeum are mounting retrospectives through January 2026.

“This show is basically a sweep to try to capture a whisper of his intrigue and greatness as best as we can,” said Diana Greenwald, co-curator of “Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory” at the Gardner. The exhibit contains over 100 works made by Crite, dating from the 1930s to the 1980s. “This is a first attempt to take a retrospective view of his work.”

The Boston Athenaeum, where Crite donated much of his artwork, will simultaneously open its show.Allan Rohan Crite: Griot of Boston,” which focuses on the works he made on paper.

“What’s really exciting is that the shows have a citywide feel,” said Greenwald. “That’s really important because Crite loved Boston and it’s nice to show that various institutions around Boston love Crite.”

This isn’t the first time multiple institutions have collaborated to honor Crite. Forty years ago, more than a dozen museums and organizations across Boston celebrated the artist’s 75th birthday with exhibits and programming. A local television special on WGBH captured some of the festivities, highlighting the love that Boston residents of all ages had for Crite.

He was born in 1910 and moved to Boston as an infant, when his parents relocated from North Plainfield, New Jersey. As a child, he and his parents resided for a time at 401 Shawmut Ave. Crite took every opportunity to observe his neighbors and draw the surrounding architecture.

“It was a record,” Crite said in a 1979 oral history interview with the Smithsonian Museum. In the interview, he discusses a drawing he did at age 10 of his home, a library and a church. “It was a way of telling a story. Because, today, 401 Shawmut Avenue still exists, but the church and 395 (Shawmut Avenue) have been destroyed.”

Crite’s mother, Annamae, encouraged him to pursue art. She was a deeply religious woman and also an art lover. She enrolled her son at the Children’s Art Center at United South End Settlements. She would take Crite and other children from the arts center to local museums to study the work of the greats.

One of their favorite places was the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “I went there and it made quite an impression. I made these memory sketches,” Crite said in the Smithsonian interview. “And one was sent to Mrs. Gardner, and the report was that she was rather pleased with it.” Crite also mentions that one day, while his mother supervised a group of children from the arts center at the museum, Mrs. Gardner saw her and invited her to tea and Annamae obliged.

“One of the things Annamae wanted for him was a career in the arts. She put him on the path that he was then to build on,” said Edmund Barry Gaither, executive director emeritus of the National Center of Afro-American Artists. He knew Crite for decades and met Annamae before she passed away in the early 1970s.

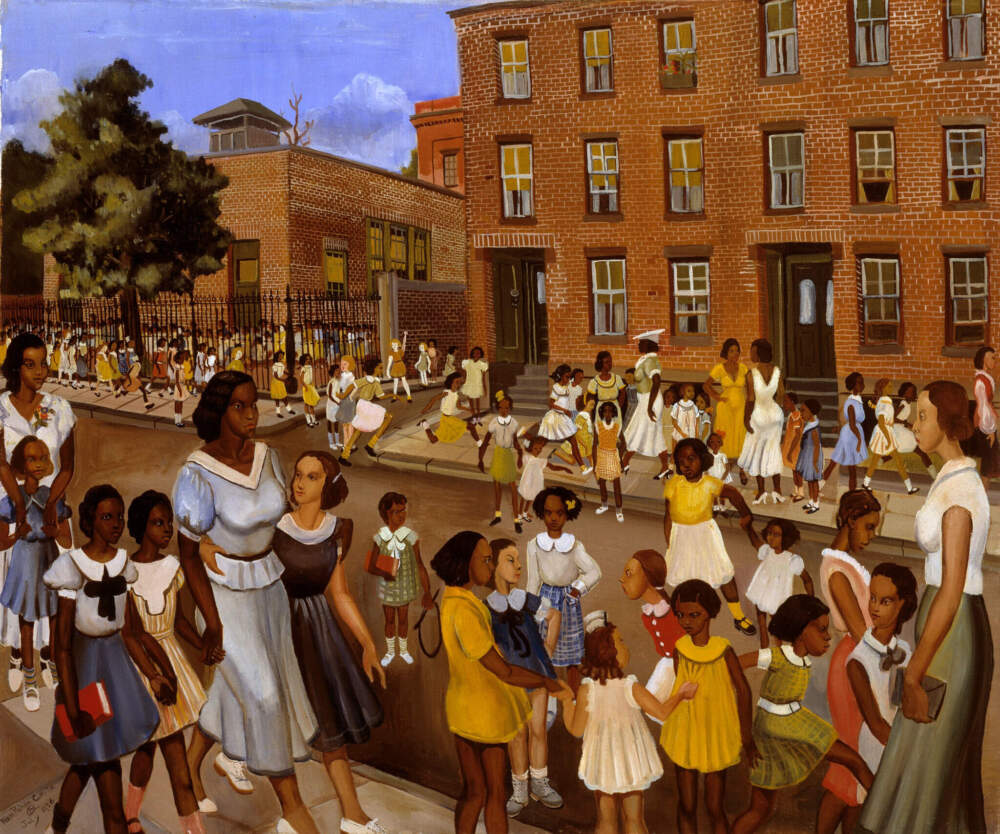

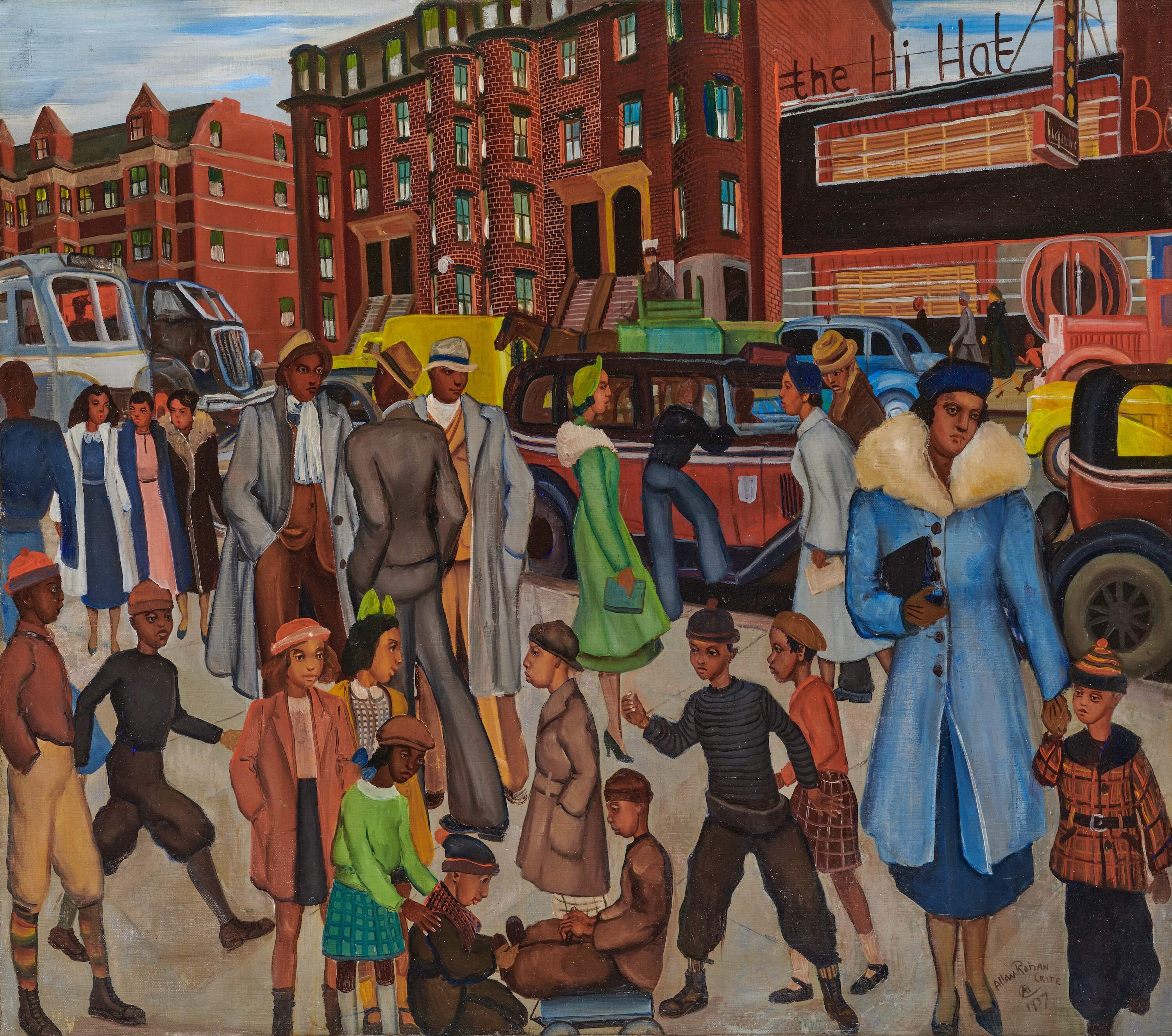

Crite attended English High School. He eventually enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts before going on to work at the Charlestown Navy Yard as an engineering draftsman. He was only in his 20s when he started creating some of the two dozen works that became part of his famous “Neighborhood Series” depicting different enclaves of people in Boston.

“Back there in the ’30s, the concept of Blacks was usually of somebody up in Harlem, or the sharecropper from the Deep South, or what you might call the jazz Negro,” Crite said in the Smithsonian interview. “But the ordinary person, you just didn’t hear about them… The idea was to establish a record, just to show the life of Black people in an ordinary setting — to show them ‘just as people’ and not a social problem.”

Crite’s thinking was essential to the general arts movement, said Gaither, because Crite’s work helped establish “Black portraiture and figures. That mattered because much of the imagery that was built around black physical presence was so distorted.”

The artist’s depictions of Blackness, particularly in his “Neighborhood Series,” portrayed the normalcy of Black life, providing insight into what Black America was really like. Many paintings show Black people going to and from church, children at play, and neighborhood events like parades and winter snowball fights. He pays special attention to the details of outfits and surrounding buildings, imbuing his works with a lifelike quality that emphasizes the humanity of his subjects.

“His work was like an antidote,” Gaither pointed out. “Essentially, the argument that Mr. Crite’s work made was that the majesty of Black people resided in their simple humanity and that they were people first.”

Professor and activist Ted Landsmark is the other co-curator of “Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory” at the Gardner. He saw Crite’s paintings before he moved from New York to Boston in the early 1970s.

“Boston had a reputation for not being particularly comfortable as a place for a person of color to move to,” Landmark said. “But Allan’s work gave me a sense of what Boston’s community was really like.” He and Crite would go on to form a decades-long friendship and working relationship.

“People see themselves in Allan’s work because they are in Allan’s work,” Landsmark said and noted the artist’s willingness to tell the stories of his subjects through his paintings and drawings.

Crite was a liturgist of the everyday and that meant something, especially to the Black community in Boston that was so frequently erased from the city’s narrative. The South End of Crite’s youth was racially and economically diverse, and that’s what he portrayed.

“Allan was a storyteller who documented daily life in a way where people could see themselves in his art,” Landmark said. “They could feel as though he was not only empathetic to their lives but willing to tell their stories.”

The South End changed drastically over the second half of the 20th century. Urban renewal efforts, which Crite referred to as “urban removal,” pushed out lower-income residents and residents of color. Buildings were demolished. “I painted these various streets, which of course have disappeared,” said Crite in a 1979 interview. “A whole way of life has vanished. Now I find the paintings have considerable value as documents.”

For this reason, Gaither said that Crite’s paintings provide important documentation of the past. “I think Crite adds evidence of the history of Blacks as a community with its own integrity. There is no America without the presence of people of color.”

Crite passed away in 2007 at age 97, but his legacy endures. This current series of exhibits exploring Crite’s life and his work demonstrates the lasting impact of a man who painted Black people back into the picture of Boston.

His paintings were a defiant gesture against the erasure of the city’s communities of color because he knew that they were worthy of being immortalized through his art — no bells or whistles required.

“Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory“is on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum from Oct. 23 – Jan. 19.”Allan Rohan Crite: Griot of Boston” is on view at the Boston Athenaeum from Oct. 23 – Jan. 24.