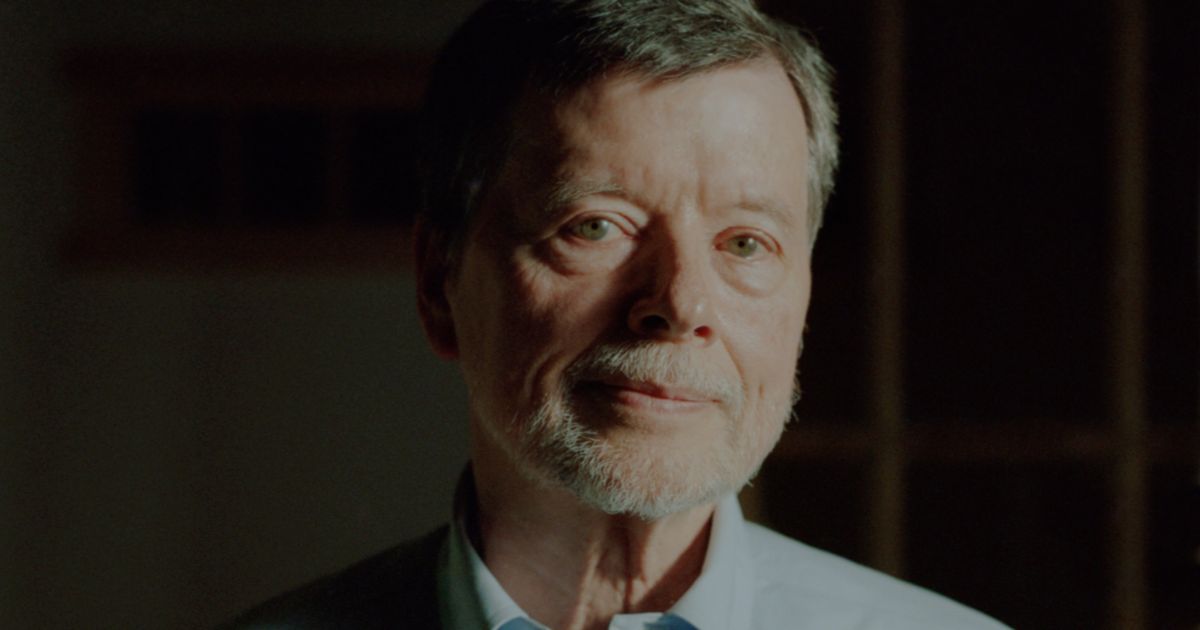

Ken Burns on ‘The American Revolution’ and PBS Cuts

Ken Burns and I have just met at Bowling Green, the tiny park at the bottom tip of Manhattan, when he brings up “all the lives that have been through here.” He doesn’t mean the tourists lined up to take selfies with the bronze bull, or anyone in the last century or even the one before that. Although he lives in New Hampshire, he’s an on-and-off New Yorker with a place in Soho and a daughter in Brooklyn, and he’s walked downtown this morning to discuss his docuseries The American Revolution, co-directed with Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt, 12 hours of lofty ideals and bloody bayoneting and the contradictions underlying “all men are created equal.” (It will premiere on PBS on November 16.) Here, in the middle of British New York, and before that Dutch New Amsterdam, is where muskets were fired and the empire had its very last outpost in 1783, after the war ended. I had been hesitant to ask Burns if he felt the presence of all those ghosts as we walked the streets. It might sound a little woo-woo, I thought. Turns out I did not need to be concerned. Before I get my first question out, he zings right into a short travelogue about what (or should we say who) he sees when he walks around his own neighborhood.

“As you go west across the streets, you get Lafayette, a general in the Revolutionary War, and then Crosby is the 19th-century philanthropist, and then Broadway — that doesn’t count — and then Mercer, a general who is wounded and dies in the Battle of Princeton,” says Burns. He’s animated by his enthusiasm, talking very fast. “And then Nathaniel Greene, probably the most important general after Washington, and then David Wooster, a major officer. Then West Broadway — doesn’t count, again, though it used to be Laurens Street — and then Thompson, a general, and Sullivan, from New Hampshire, where I live, a very important general in the Battle of Long Island, the biggest of the war, but is also part of the extermination of the Indian villages in the Haudenosaunee and upstate. And then there’s Varick, also a general, and then Hudson and Washington.”

It’s the high-energy spoken equivalent of a 30-second pan across a 19th-century map, and he’s gone barely halfway across town. I half expect a solo minor-key violin to kick in.

That manner of activation of a still image, now widely known as the Ken Burns Effect (thanks partly to Apple iMovie, where it’s a menu option), is a powerful way of retaining a viewer’s gaze for much longer than a static shot otherwise might. It’s fundamental to the experience of Burns’s films: sustained scholarly commentary, the gradual accretion of fine detail, and the intimately mic’d narration incorporating primary sources (especially diaries and letters, read by the likes of Meryl Streep), all in the service of the bigger story, of ideals crafted and crushed, republics born and torn apart, leaders who are perceived as marble statues but in real life are flawed and complex.

He says that he looked up one day as his team was finishing the Vietnam documentary that came out in 2017 and said, “Okay, we’re doing the Revolution next.” Donald Trump was coming to power, so thoughts of imperial rule were perhaps on Burns’s mind. Even though he’s already covered the Civil War, World War II, and Vietnam, the Revolution felt like a particularly huge undertaking, and “I knew I needed to be farther along in my professional life to have the chops.” (He’s 72 now.) It has been cooking for a decade, all while he’s been completing at least eight other projects, including Benjamin Franklin and The U.S. and the Holocaust. It was, he says, dumb luck that The American Revolution came together just in time to mark (a) the 250th birthday of the nation and (b) the swerve to autocracy cloaked in red, white, and blue that we’re living through.

Unlike most of his other films, this one required some inventive solutions to the historical documentarian’s core problem, which is that the further you go back in time, the scantier the available material becomes. For The Roosevelts and World War II, Burns had newsreels; for The Civil War, he could employ the photographs of Mathew Brady along with illustrations from the likes of Harper’s Weekly. This time around, there are only so many paintings and printed broadsides to send the camera gliding across. That was also true during Burns’s Benjamin Franklin project, but “that was with a central figure who had his portrait painted many times,” he says. “This story introduces us to literally scores and scores of people who didn’t, who then have to be brought alive.” Among other things, he uses finely rendered watercolors of the battle scenes, some of which existed before the film and others that his team commissioned.

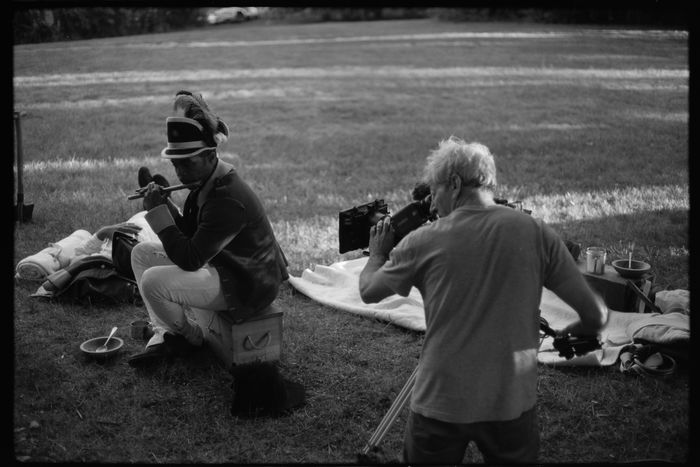

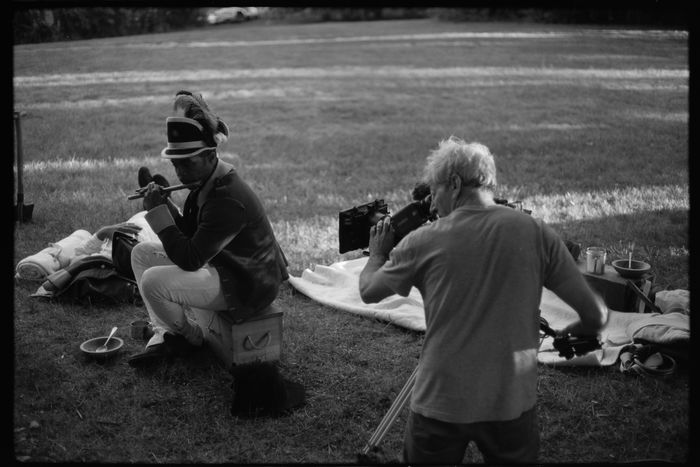

There are also reenactors in costume, which is a little unexpected. Many documentarians are disdainful of such performances, and Burns avoided working with them on The Civil War. “They kind of had, for me, a cartoony thing,” he recalls. This time was different, partly because “you realize how deadly serious they take it.” (It helps that, although there is plenty of racism baked into the story of the American Revolution, there isn’t a lost-cause mythos. Very few Americans pine for the days under the Crown.) “So I said, we’re going to follow reenactors and shoot them impressionistically. And in many points, some of our visual solutions are because they didn’t want our cameras anywhere near them. We would say, ‘We can fly a drone.’ And they go, ‘Yeah, but not low. No, not that low.’” Many of those scenes, as a result, are near-abstractions that still tell a pivotal part of the story. A brief shot of a Black-skinned hand on a gun reminds viewers that thousands of fighting men, both Tory and rebel, had been or were enslaved. An arresting and beautiful overhead shot of a line of soldiers advancing unevenly across the emerald grass and brown dust of a field in New Jersey frames the first episode’s title.

High above a New Jersey battle site, via drone.

Photo: Courtesy of American Revolution Film Project/Florentine Films

So much of what happened here in New York City is seen mostly in maps and watercolors. George Washington’s retreat from Brooklyn after the Battle of Long Island, which almost throttled the Revolution in its cradle — “after a gigantic tactical error,” Burns explains — crossed the spot where we are standing in lower Manhattan. But not everything has been paved over. He gestures to the ironwork around Bowling Green, where, he points out, there once stood a statue of King George III. “Early in the resistance,” he says, “the colonists were getting so upset that the British put a fence around the statue. It didn’t stop some patriots from shooting him through the cheek.” And then, in 1776, came the revolt: After the newly signed Declaration of Independence was read out to Washington’s troops, the rebels “pulled the statue down.” It broke into shards, most of which soon went up to a foundry in Connecticut to be recast into bullets to be fired back at the British. One magazine of the day suggested that the ammunition would “assimilate with the brains of our infatuated adversaries.” Burns, off the top of his head, tells me that the statue was turned into “42,088 bullets.” That scene (and that number), along with thousands of other such details, makes its way into The American Revolution.

A related point comes up a couple of times in our conversation: the desire to avoid Revolutionary War kitsch. The last thing you want in a film like this, as Burns puts it, is “the kind of romantic, encrusted-with-the-barnacles-of-sentimentality story” a lot of us recall from the schoolroom, of Betsy Ross’s stitchery and the British generals’ haplessness and Washington’s I cannot tell a lie. “But you can get rid of the cherry tree and the wooden teeth and a lot of other mythologies and replace it with Washington’s own words — that gives him a gravitas, and we have an appreciation for his ability to move ordinary people to fight in the dead of night, to be able to pick subordinate talent without fear of being overwhelmed by their intellect,” he says.

Our talk of the first president eventually pivots to the actions of the current one. Burns, after all, is one of the success stories of public broadcasting, in the pantheon with Bill Moyers, Julia Child, and Big Bird. After 30 years’ worth of attempts to defund PBS, the Trump administration and its congressional allies have finally managed to carry it off, effectively dismantling the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The National Endowment for the Humanities, which has backed many of Burns’s films, is likewise under threat. Without their grants in his early years, “we wouldn’t have been able to make it.” (As it happens, 30 years ago, when PBS funding was under a previous existential threat after the Gingrich Congress swept in, I interviewed Child about this very subject, and she offered a prescient and similar reading. “This new group of people seems to want to dismantle everything that’s taken so long to build up,” she told me in that singular voice. “What’s so deadly liberal and horrible about teaching people drama and singing? The thing is, if you’re far off in North Dakota — saying it’s elitist is a very elitist thing itself, saying that only the rich can enjoy theater. It should be available to everybody!”)

Burns will be able to continue working, of course, owing to his long-standing reputation — “We’ll survive; PBS will survive” — but even he will feel these cuts. The American Revolution was only partially backed by corporate and independent donors. Apart from one single-sponsor project 40 years ago, “I’m having a hard time thinking of any film that doesn’t have CPB money in it. I had $4 million in authorized and appropriated funding for a project, LBJ and the Great Society — gone,” he says. Like Child, he’s most concerned about the loss to communities where PBS is one of the only good media sources around. “They’ll become news deserts, essentially. It’s so sad because of the damage it will do in Alaska, the Dakotas, eastern Tennessee — communities in which PBS isn’t just children’s and prime time, but it’s continuing education, warning systems, homeland-security stuff,” he adds.

Shooting at Colonial Williamsburg and on a long-ago battlefield. Photo: David Schmidt; Edgardo Gonzalez.

Shooting at Colonial Williamsburg and on a long-ago battlefield. Photo: David Schmidt; Edgardo Gonzalez.

The use of reenactors was an unusual choice for Burns: “You realize how deadly serious they take it.” Photo: Mike Doyle; Graham Deneen.

The use of reenactors was an unusual choice for Burns: “You realize how deadly serious they take it.” Photo: Mike Doyle; Graham Deneen.

The right-wing argument has been that there are far more outlets available to a young filmmaker today than there were when Burns shot Brooklyn Bridge, his first feature, in 1981. Perhaps so, but he has seen the business from the inside, and he knows what streaming and cable outlets do and do not offer. The American Revolution “took ten and a half years to make and cost 30 million bucks. I spent ten of those ten and a half years raising the 30 million bucks. At that point in my professional life, I could have gone to a streaming service or to premium cable and gotten the $30 million probably in one afternoon, in a pitch. But they would not have given me ten and a half years, and there would’ve been suits at every level, writing notes and whatever. And that’s the difference. These are all director’s cuts, and they all have the ability to breathe,” he says.

Burns (lower right) and his team at work on The American Revolution.

Photo: Loren Howard

We’ve been walking up Broadway from Bowling Green as we talk, and now we’re in Trinity Church’s yard, where we pause in front of the tomb of Alexander Hamilton. You don’t talk about him too much in the new series, I remark. “No, we didn’t — he shows up seven or eight times, at really particular moments. But he is indelibly marked by one of the greatest cultural phenomena of this century,” Burns says. He smiles at the thought of Hamilton — as Burnsian a piece of musical theater as one could ever imagine — and we look down at Eliza’s grave marker, next to her husband’s: “My youngest is at school in Connecticut, and, you know, she can recite the entire thing.” He pulls out his phone. “I have to take a picture for her. Or, actually, a movie.” Whereupon he turns his phone to “landscape orientation,” and with a steady hand frames Alexander Hamilton’s name and epitaph, hangs on it for a moment, and then — I am not making this up — does a slow Burnsian pan down to Eliza’s. He presses “send.” A moment later, a heart emoji pops up, and his daughter FaceTimes for a moment to thank him.

We turn south along Broad Street as we near the end of our conversation — passing Federal Hall, the site where Washington was inaugurated and Congress met for the first time, and walking down toward Fraunces Tavern, where Washington bid a teary good-bye to his officers — and Burns returns to the challenge of getting into the heads of those ancient figures. “How could they possibly feel? Plus, what’s with the buckles on the shoes and the hose and the waistcoats and the powdered wigs? So clearly they’re not like us. Well, of course, they’re exactly like us,” he says. And then he starts ticking off turning points in the film, all of which sound curiously contemporary: “There’s a failed invasion of Canada.” His enthusiasm kicks in and he starts talking even faster. “There’s a continent-wide pandemic that kills more people than the Revolution did. Come on! There’s arguments about inoculation. Come on! You can’t make this stuff up.”