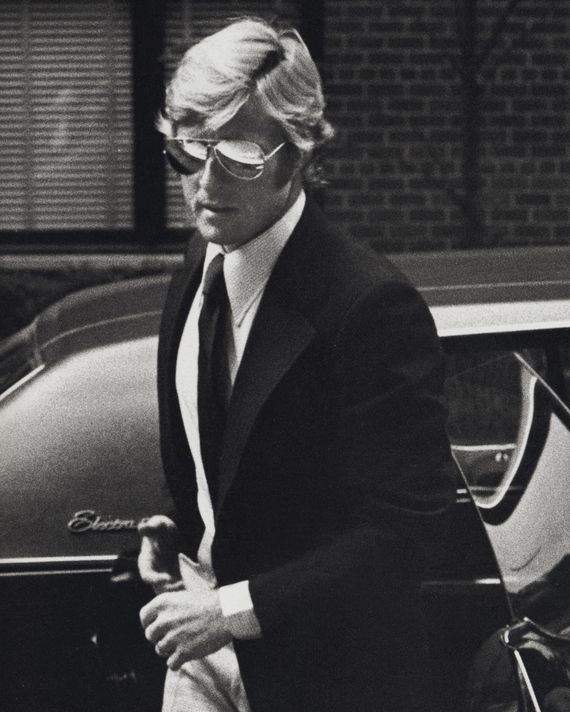

Redford’s coiled energy and easygoing elegance were entrancing.

Photo: Ron Galella/WireImage

There’s a moment in the 1975 Sydney Pollack thriller Three Days of the Condor that captures what made Robert Redford one of the great movie stars. Redford’s Joe Turner is a bookish CIA analyst who leaves the office for lunch one day and returns to find that all of his colleagues have been murdered. He then goes on the run, forcing a photographer, Kathy Hale (Faye Dunaway), to let him use her basement apartment as a safe house. Then her doorbell rings. It’s a mail carrier who says he has a package for her and she needs to sign for it.

Kathy is in the shower when the doorbell rings. Joe’s in the kitchen. He and the postman make eye contact through Kathy’s front window. Joe says Kathy’s not home and to leave the package on the stoop. When the carrier tells him, “Well, you can sign,” Joe lowers his guard and steps outside. When the man’s cheap pen doesn’t work, Joe goes back inside to find another. What saves Joe’s life is a brief backward glance that takes in the man from head to toe, ending on his shoes: tan suede with leather laces and racing stripes, definitely not the clodhoppers postmen wore in the ’70s. As Redford moves from the background into a close-up, we see a chain of thoughts race through his character’s mind, ending with a look of horrified clarity. The movie cuts from the assassin pulling a machine gun from his bag to Joe hurling a pot of hot coffee at him, igniting a close-quarters battle that trashes the place. Though the scene unfolds at incredible speed, Redford makes it legible as well as believable. He takes us from “something is amiss” to “postmen don’t wear shoes like that” to “I must kill him” in three seconds and four footsteps.

Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor (1975).

Photo: Everett Collection

Redford, who died yesterday at 89 at home in Provo, Utah, was a legend on multiple fronts. In addition to his acting, he founded the Sundance Institute to champion independent film and then its eponymous festival. His original goal was to help emerging filmmakers avoid the setbacks and indignities he had faced in the late 1960s when he shepherded the skiing drama Downhill Racer, his first project as both star and producer, through the remnants of the old studio system. He produced and directed eight features, the best being his multiple-Oscar-winning directorial debut, Ordinary People, about repressed Wasps struggling to grieve a death in the family. Redford directed two other exemplary films about repressed people coping with loss: A River Runs Through It (starring Brad Pitt in a doomed-golden-boy role Redford would’ve crushed in the ’60s) and The Horse Whisperer. He also made the ethics drama Quiz Show, about the cheating scandal that rocked NBC’s Twenty-One in the 1950s when Redford was a theater student in New York. “The actor in me looked at the show and felt I was watching other actors,” he told the Los Angeles Times. It’s a film organized around the idea that acting is a part of life.

But just a part. As a celebrity, Redford was the total package: an avid reader, an outspoken political activist (mainly on behalf of Native American rights and environmental protection), and an all-around athlete who skied, swam, sailed, rode horses, and played baseball, football, and tennis. He used all of it as raw material for performances and a reference point in directing other actors. His well-roundedness gave range to an artist who was so handsome he had no choice but to lead with his looks.

Redford’s coiled energy and easygoing elegance were entrancing. You believed this goldenest of golden boys as soulful rancher (The Electric Horseman, The Horse Whisperer), an Olympic-caliber skier (Downhill Racer), a vengeful mountain man (Jeremiah Johnson), a war veteran turned respected writer (The Way We Were), a CIA desk jockey (Three Days of the Condor), a pioneering computer hacker with unshakable countercultural values (Sneakers), a lone sailor trying to survive a shipwreck (All Is Lost), a supercool diamond thief (The Hot Rock), and a comic-book boss (Captain America: The Winter Soldier).

The screenwriter William Goldman, who composed or contributed to five of the star’s ’70s films, theorized that Redford and his contemporary Clint Eastwood “were so terrific (because) they didn’t make it early. Eastwood was still digging swimming pools when he was 29.” Redford gave many solid performances in the first few years of his film career, but it was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, produced when he was already into his 30s, that made him a movie star. Written by Goldman and directed by George Roy Hill, it perfected the buddy movie: a rollicking western starring Paul Newman as the sardonic, world-weary Butch and Redford as the Kid, a prodigious gunslinger with a hot temper. It was a career-defining role, a quiet killer, nearly an antihero. In one scene, when the Kid is accused of cheating at poker, Hill holds on Redford’s face in close-up for 60 seconds — an eternity for a Hollywood studio picture, even then — as Newman tries to de-escalate. Save for a quick glance at his adversary, Redford fixes his eyes on the out-of-focus holster in the foreground, a cobra waiting to strike. Finally, the Kid stands up and heads for the door. We think Butch has talked him off the ledge until he turns back, blasts the man’s gun from its holster and makes it skip across the saloon floor.

1969 was a pivotal year for Redford. Along with Butch Cassidy, he co-starred in the turn-of-the-century anti-western Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here. It was the year he proved himself as an actor-producer with Downhill Racer, putting together the director Michael Ritchie and screenwriter-novelist James Salter, traveling Europe with the U.S. Olympic ski team, and doing most of the onscreen skiing himself. The result was appreciated mainly by art-film devotees, but it further showed Redford was both charismatic enough to anchor a feature and serious about cinema. Butch Cassidy’s success transformed him overnight into a star who could get a film funded just by saying “yes.” But it wasn’t always easy to get a “yes” from Redford. He became notorious in the industry as a passive-aggressive idol who dragged directors and writers through years of rewrites and recastings before cutting them loose. Still, everybody wanted to work with him because he knew what kinds of characters moviegoers wanted him to play, and he managed to satisfy them while seeding every performance with surprising choices. He started shaping his screen persona early, and it did not have room for the sad dreamers and grubby losers so many ’70s stars were drawn to. The 1970 picaresque comedy Little Fauss and Big Halsy would mark the last time Redford played a chronic screwup: a womanizing dirt-bike racer and petty manipulator who gets banned from competition for drinking at a track. He did the movie to settle up with Paramount, which had sued him for trying to get out of a three-picture deal.

After that, Redford typically played men who were obsessive, arrogant, uncompromising, or just hard to reach, but rarely a person who was just flat-out bad at something. Redford had always been on this path, even if he didn’t yet know it. One of the most repeated Redford anecdotes is about Mike Nichols interviewing him circa 1966 to play the lead in The Graduate, disillusioned sad sack Ben Braddock, who has an affair with Mrs. Robinson, the mother of his beautiful young neighbor. After a few minutes in Redford’s presence, Nichols admitted he was having trouble picturing him as “a loser.” “I can play a loser,” Redford insisted. Unconvinced, Nichols said, “Okay, have you ever struck out with a girl?” Redford stared blankly for a moment, then asked, “What do you mean?”

Hill reteamed with Redford and Newman on the Depression-era caper The Sting, which became the second-most-successful film of 1973 after The Exorcist, won seven Oscars, and earned Redford his first and only Best Actor nomination as nimble con man Johnny Hooker. He lost — but it was, as they say, an honor to be nominated, especially considering his competitors were Al Pacino for Serpico, Marlon Brando for Last Tango in Paris, Jack Nicholson for The Last Detail, and the victor, Jack Lemmon in Save the Tiger. (Ironically, Lemmon was mainly a light comedian who hadn’t played a role that dark since 1962’s Days of Wine and Roses, while Redford’s early rom-coms prompted some critics to call him the next Jack Lemmon.) In The Sting, Redford’s classy man-of-action mode got a period makeover courtesy of costume designer Edith Head, who outfitted him in dazzling bespoke clothes including a plum two-piece suit with red and ivory pinstripes and two-tone shoes that clacked so loudly on the back-lot cobblestones they made the movie feel like a musical without the musical numbers. With its emphasis on the long con as an elaborate performance complete with lines, sets, and rehearsals, The Sting is one of the great films about looking and being looked at (a recurring theme in Redford’s filmography). It also showed that the pupil from Butch Cassidy had surpassed the master: Newman’s role as the alcoholic con man Henry Gondorff was a glorified supporting part, gifted to him because his career was in a slump and Redford wanted to pay him back for handing him his big break. Timeless and endlessly rewatchable, The Sting made Redford one of the biggest stars in the world.

Lethal Redford was showcased in 1972’s Jeremiah Johnson, a film much rougher than the meme it spawned — a bearded Redford nodding with approval — would suggest. It was directed by Pollack, Redford’s creative partner on seven films starting with This Property Is Condemned and stretching through 1990’s misbegotten Havana, a riff on Casablanca with Redford in the Bogart role. Pollack and Redford’s streak was unmatched by any other actor-director team except perhaps Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese, whose Raging Bull lost the 1980 Best Picture and Director Oscars to Ordinary People. (The latter is often characterized as a grave injustice, but there were no hard feelings. Scorsese has always spoken highly of Redford’s filmmaking, and Redford directed occasional actor Scorsese to one of his best-ever screen performances as the politely menacing president of Geritol in Quiz Show.) Redford and Pollack seemed to have similar temperaments and priorities. Both came to producing and directing through acting and had better eyes for composition than many other actors who jumped the fence. (Redford, notably, studied painting in his youth.)

Pollack’s 1973 film The Way We Were was a hugely popular historical romance starring Barbra Streisand as the passionate leftist Katie Morosky and Redford as the straitlaced conservative Hubbell Gardiner, their great romance destroyed by politics. Here, as in a lot of Redford’s love stories, the film belongs mostly to the leading lady. Redford’s main tasks are to look just as fabulous as Streisand, gaze upon her adoringly, and make sure his character stays likable despite his McCarthyism. Redford accomplishes all three with his characteristic lack of fuss. The entire production is ennobled by his gift for listening actively to scene partners rather than waiting for his turn to speak. Grand, usually doomed love stories would become a Redford specialty, all the way through to one of his last performances, in 2017’s Old Souls at Night.

Redford and Streisand in The Way We Were (1973).

Photo: Moviestore/Shutterstock

The actor’s biggest ’70s bomb marked the last time a Redford character was permitted to catastrophically fail: the 1975 barnstorming adventure The Great Waldo Pepper, a Redford-Goldman-Hill project in which the star played a World War I veteran turned daredevil who calls himself the world’s second-greatest flyer. Redford blamed the film’s commercial and critical failure on a horrifying scene in which Pepper convinces a would-be wing walker (Susan Sarandon) to perform with him only to watch helplessly as she falls to her death. Goldman himself openly conceded that, whatever its value as a bold tonal shift at the film’s halfway mark, it lost the audience who came to see Redford triumph. Waldo Pepper would be his last teaming with Hill and Goldman. The aftershock of its total rejection by audiences reverberated through the rest of Redford’s career, making him reluctant to risk losing the viewer’s sympathy again.

His rebound, the 1976 Alan J. Pakula thriller All the President’s Men, was an all-timer in which Redford played Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward opposite Dustin Hoffman’s Carl Bernstein. Redford bought the screen rights to the duo’s manuscript about their reporting on the Watergate scandal when it was still a work-in-progress, and he influenced the final draft by suggesting they concentrate less on the big picture than on the detective-story aspects and the men’s tetchy but mutually respectful relationship. The movie would not have existed without Redford leveraging his box-office clout to get funding for a project centered on guys in ties talking on the phone as recent history unfolds around them. Redford infuses those scenes with subtext, tension, and dry humor. His performance as Woodward was the compass that helped his collaborators find true north.

Redford’s great decade crested in 1979 with the production of Ordinary People, the creation of Sundance, and his second teaming with Jane Fonda, The Electric Horseman, another Redford-Pollack project. Redford played a rodeo cowboy turned cereal pitchman who goes on the run with an abused horse. The 1980s found Redford refocusing his energies with acting and filmmaking taking a back seat to his very public activism on behalf of Native Americans and environmental protection and his leadership of Sundance. Later in life, Redford complained to friends that he’d made a dozen movies in the ’70s but only a few in the ’80s. He told film historian Peter Biskind he feared his presence as a celebrity front man pulled focus from Sundance itself and became “a distorting force, a liability.” He also realized he wasn’t getting any younger and there were still “things I want to do and films I want to make … It was never my intention to quit my career and run Sundance.” His handful of ’80s pictures included some big successes, notably the multiple-Oscar-winning Pollack film Out of Africa, a melodrama set in 1913 Kenya co-starring Meryl Streep. The movie won seven Oscars, including Best Picture, and did well at the box office despite a poky pace and a three-hour running time.

Out of Africa also (deservedly) got Redford the worst reviews of his life. Even if he’d been able to do the accent, the part didn’t accommodate the keen intellect Redford radiated. Middle age was an awkward growth period with Redford accepting too many roles that used his star power to disguise other problems and that seemed afraid of making him vulnerable or calling attention to the realities of age. That’s why the 1984 baseball movie The Natural is heartbreaking and relatable when Redford’s over-the-hill comeback kid, Roy Hobbs, has everyday conversations but embarrassing when it drowns then-47-year-old Redford in soft lighting and junks the corrosively bleak conclusion of Bernard Malamud’s novel so Roy can deliver a pennant-winning homer and an upbeat ending. The bigger and more abstract the character, the less appropriate Redford’s casting seemed. The nadir might have been Indecent Proposal, in which he played an enigmatic tycoon who offers Demi Moore a million dollars to sleep with her, tormenting her husband (Woody Harrelson) and peevishly continuing to disrupt their lives afterward. Part of the problem is the material — sleaze posing as a thought prompt — but another is Redford’s aura. It was hard to reconcile an actor who had played so many men of principle doing something so gross.

He found a new center of gravity in the ’90s, a decade when his best performance was his most uncharacteristic. In writer-director Phil Alden Robinson’s Sneakers, he played another legendary man, though thankfully a human-scale one: cybersecurity expert Martin Bishop, a keyboard-warrior James Bond. A caper with high-tech trappings, Sneakers let Redford ping-pong Robinson’s snappy dialogue with a formidable ensemble that included Sidney Poitier, Ben Kingsley, and River Phoenix (in one of his final films). It also mined laughs by casting Redford in a role where he could do daring and clever things but had trouble expressing basic feelings and even more difficulty under pressure. A highlight puts Martin in a bluffing situation in which he must repeat information being fed to him through a hidden earpiece. It’s a Cyrano de Bergerac lift that lets the star be self-deprecating and display a previously unseen gift for nervous stammering. Better still is a crowd-pleasing moment near the end when Martin gets the drop on a goon who has repeatedly tried to kill him. He pauses for a moment as if realizing this is the point when a cool movie hero would make a pithy quip, but he can’t think of one so he grunts in frustration and brains the guy with the butt of his gun.

Unfortunately, too many of Redford’s later roles seemed to lean on his finely honed image as the supercompetent, super-handsome man of principle, including The Last Castle, which cast him as a military prisoner presented as a cross between Rambo, The Fountainhead’s Howard Roark, and a missing Kennedy brother. There’s a sequence in which the warden (James Gandolfini) tries to break Redford’s character by forcing him to carry heavy stones across a courtyard, but he endures and is rewarded with the other convicts’ applause. The scene seems to exist mainly to show that, at 64, Redford was still ripped. The Tony Scott espionage thriller Spy Game reteamed him with Brad Pitt — one of many younger actors who had been called “the next Redford” — but locked him into a generic techno-thriller mentor role and didn’t tap Redford’s ability to put across the rueful wisdom of an aging badass.

He did bring that persona out in high style opposite Sissy Spacek in 2018’s The Old Man & the Gun as a gentleman bandit, and even more so in All Is Lost, a small-scale disaster film from J.C. Chandor. It has just one character, Redford’s unnamed sailor, whose damaged yacht sinks in a storm, leaving him adrift in a raft on the ocean. It’s a survival story like Jeremiah Johnson, and it’s one of Redford’s greatest roles and deepest performances; featuring just 51 words of dialogue, the film lets the star perform feats of strength most younger men could only dream of and trusts him to communicate every flicker of fear, determination, and regret with his face and body alone. More so than any of his later projects, All Is Lost puts his athleticism in service to an existentialist story about the struggle being the point of life’s journey, which has the same ending for everybody. In a 2013 New York Times interview, Redford encapsulated the simple reason for this character’s motivation, which could serve as a summation of his own life’s work: “You just continue. Because that’s all there is to do.”