‘There Was, There Was Not’ Helmer Emily Mkrtchian On Artsakh War Doc

Filmmaker Emily Mkrtichian didn’t know she would be making a war documentary when she embarked on her near-decade-in-the-making feature There Was, There Was Not. What began as a project aiming to explore the lives of four disparate women in post-conflict Artsakh changed almost overnight as the long-beleaguered breakaway state, sandwiched between Azerbaijan and Armenia, became the site of ethnic cleansing of its indigenous majority Armenian population in the wake of a major escalation in a dormant conflict.

“Everything was totally confusing and scary,” the documentarian tells Deadline in an interview. “And at that moment, I understood that the film that we were making was absolutely going to change, but it took several years to understand what that meant, and so I stayed through the whole 45 days of the war.”

Toward the latter half of 2020, as international borders slowly reopened, Mkrtichian was preparing to wrap up filming on the doc. The day before she was set to fly back to the US, the war broke out after an Azerbaijani offensive. “It was absolutely a coincidence and a shock to be there with a camera when that was happening,” she says.

There Was, There Was Not — which had its world premiere at the all-documentary festival True/False last year and will continue screening in certain US cities through November following an Oct. 10 release — takes its name from the traditional introductory phrase in Armenian folk tales, the corollary to the English variant “Once upon a time.” With establishing shots of the majestic Armenian highlands, the documentary makes a concerted effort to trace the deep-rooted mythos of this ancestral land before delving into its subjects.

“In the years that followed, it was really hard as an artist, as a filmmaker, to feel responsible for creating a narrative or making some sort of meaning out of that experience,” Mkrtichian recalls of filming. “And for me, that experience was fundamentally witnessing Siranush, Sose, Gayane, Sveta in that unbelievable moment of their lives… It took me a really long time to try to figure out what it is we’re doing when we tell stories, and how that can still have power, even if it feels like all of our power has been taken away.”

The doc was born partially out of a short film Mkrtician had previously released in 2018, Motherlandabout women in the capital city of Stepanakert who served with the HALO Trustan NGO that works on clearing landmines and explosives in conflict areas. Through that project, and her split time between Armenia, Artsakh, and the US, she came to know Siranush Sargsyan, an educator-turned-freelance war correspondent; Gayane Hambardzumyan, a feminist organizer; Sose Balasanyan, a rising judo star and world champion; and Sveta Harutunyan, a deminer with HALO.

Siranush Sargsyan in ‘There Was, There Was Not’

“The film is not meant to garner sympathy and for others to watch it and to think of these women as victims,” Mkrtichian maintains, “because I have learned so much from these four women about survival, resistance, resilience. I think, if anything, the film is trying to tell us that these women have something to teach us. They’re not there for us to feel bad for; we can be enraged about what happened, and we can understand that it was a huge injustice, but it is not meant to flatter them nor humans.”

To that end, Mkrtichian, as an Armenian diaspora, was cognizant of the “different privilege” she brought to the material, choosing to ground the film in reality and lean away from sensationalism. As such, the director made “very intentional” choices to include moments where she crosses the boundary between filmmaker and subject, appearing on screen in intimate scenes to share an embrace or offer some words.

“It was important to allow something of the relationship of myself to these women, it was important for the viewer to understand that the person behind the camera really cared about them,” she explains.

Additionally, Mkrtichian was keen to eschew conventions of the war documentary subgenre, making the deliberate decision to depict the “rupture” that occurs at the outset of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and breaking with the “vérité” of the film to conduct sit-down interviews.

“When we were in the edit, there was a lot of talk around — the traditional version of this film would have started with bombs, so that people knew that there was a conflict coming and that they could stay engaged and interested,” she says. “And it was a very intentional choice to spend the first 40 minutes of the film in Artsakh, in a place that, of course, isn’t perfect, because all these women were struggling for something different, but also was so beautiful in its own way.”

The women’s distinct and all-encompassing tie to their homeland — despite its conservatism and embedded misogyny, as Sargsyan points out — is something Mkrtichian admits she was envious of, having “felt disconnected from the place that I grew up in.”

“Their love of Artsakh was really palpable… I was, like, jealous of that,” she says. “There was something there that really captivated me, that knowledge of your connection to a place, and being able to still be on it despite everything around being kind of tenuous, and somehow that almost made you love it more.”

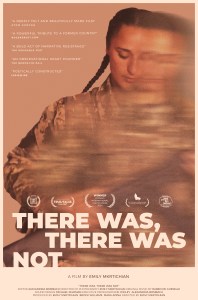

Official poster for ‘There Was, There Was Not’

In keeping with the rich Armenian tradition of generational storytelling — Mkrtichian says, “I was raised on stories of genocide. I was raised on stories of, ‘Be careful, be cautious.’ I was raised on stories of, ‘Land is important, family is important.’” — the filmmaker wanted to explore, through the prism of warfare, the meaning-making of oral histories.

“Experiencing the war was almost, to me, like experiencing these things that I had heard through stories, and it made me think about, ‘What is the value of these stories? Why were they passed on to me? And why are they so important in my childhood?’ And part of it is because they were passing on information, and they were also keeping something alive that had been lost to my ancestors,” she says.

The war officially concluded Nov. 10, 2020, when Russia brokered a ceasefire agreement in favor of Azerbaijan, whose use of banned Israeli-made cluster bombs and other evolved munitions led to the death of over 5,000. Despite a peacekeeping force, Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive on the sovereign territory in September 2023, which led to the displacement of nearly the entire Artsakh population, some 120,000, to Armenia. Shortly thereafter, in January 2024, the disputed region was officially dissolved and the republic ceased to exist. or peace deal is currently in effect between the two nations.

Mkrtician hopes her film exists in concert with other projects that offer “resistance to erasure” via the “work of memory.”

“It feels difficult to live in the world and look around at how many people are being forcibly displaced from their lands,” she says. “I want (the film) to keep (this place) alive. And I want it to really be in solidarity with all the other struggles of the other peoples who are fighting to stay on their land, so we understand: Why is that important, and what is the real risk? There’s a real risk of losing those places forever.”

(LR) Sveta Harutunyan, Sose Balasanyan, Gayane Hambardzumyan and Siranush Sargsyan in ‘There Was, There Was Not’

For Sargsyan — who is currently enrolled in the human rights advocacy program at the Nova School of Business & Economics in Carcavelos, Portugal — shedding light on the understudied conflict is a “way of life … I just can’t do it.”

“I was not heard. I was not seen. And I think one of the biggest, (most) important part(s) of this movie is that it allows us to be seen,” she explains in an interview, adding that the movie stands against those trying to “destroy your past.”

Of combatting historical deletion, she says, “You feel insecure about your past, what you experienced there. And sometimes you also even start to ask, like, ‘Maybe that wasn’t real.’”

Particularly “traumatic,” Sargsyan says, is the insinuation from other Armenians — whether government officials or civilians — that the Artsakhi populace “didn’t fight” back hard enough to protect its territory.

“We are unusual refugees, like we are refugees in our country, in our homeland,” she says of relocating to Armenia, noting “our love was unconditional to Artsakh” and “we did our best.”

“Now I live in one of the (most) beautiful cities in the world (in Portugal), but it’s like a movie: You are walking and you know, like, it’s not your life. It will never be your life,” she explains.

Despite the “very painful” nature of the loss, Sargsyan says Artsakhis now consider Armenia their adoptive homeland, where the work of protecting their identity and history will continue.

“What we had, we have to keep it, especially when we don’t have any kind of access to Artsakh,” she states. “Every scene, every shop, even every dog — I don’t know — everything you see in (this) movie, it’s important. For me, it’s like a museum, because we will never be that way again. We all changed. We are not the same people, and we will never be in that environment.”